RON HENGGELER |

September 21, 2018

Impressions from the Cantor Arts Center and the Anderson Collection at Stanford University, the Stanford Mausoleum, and Dr. Jane Goodall at a Ted-X Talk in Palo Alto

On Wednesday September 12th, Dave and I spent the day at Stanford University in Palo Alto. In the evening we attended a Ted-X Talk at Palo Alto's JCC where Jane Goodall was speaking. Here are my photos from the day.

A jar's headdress in the window of the round room at home. |

A jar and its headdress containing artifacts from the restoration of the 1905 Murphy Windmill in Golden Gate Park. |

The entrance to the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University |

The entrance to the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University |

|

A telegram from Jane Stanford to Mark Hopkins expressing the loss of their son Leland Jr. to Typhoid Fever. |

The Stanford Family Room at the Cantor Arts Center |

Technology & Interior AestheticsFrom building the railroad that connected a growing nation to supporting the experiments in photography that laid the groundwork for motion pictures, the Stanfords were champions of technological progress. Their interest in emerging technologies was evident throughout their household: photographs hug on the walls (whereas other elites would show only traditional paintings) plus a photo-viewing contraption--the Megalethoscope--featured prominently in their living room.Megalethoscope 1866-1867Wood, metal, and glassby Carlo Ponti Italy, c. 1823-1893 |

|

Jane's JewelsIn 1899 Jane commissioned a painting of her jewels to inventory the small treasures before they were put up for auction. They were then sold to support the university library. Formally established in 1908, the Jewel Fund still provides significant resources for library acquisitions that bolster the research interests of Stanford faculty and students; books purchased therough the fund bear a Jewel Fund bookplate. (The Jewel Society founded in 2007 now encompasses other sustaining funds that support library acquisitions.) |

|

Tiffany & Co.Renaissance Revival Clock c. 1876From the Stanford Family Collections |

|

|

Portrait of Senator Leland Stanford1884Oil on canvasBy Léon Joseph Florentin BonnatFrance, 1834-1922 |

Leland Stanford Jr.1884Oil on canvasBy Léon Joseph Florentin Bonnat France, 1834-1922 |

|

Leland Stanford1881Oil on canvasBy Jean-Louis-Ernest MeissonierFrance 1815-1891 |

|

Jane Lathrop Stanford1881Oil on canvasBy Léon Joseph Florentin BonnatFrance, 1834-1922 |

|

|

Portrait of Leland Stanford Jr.1884Oil on canvasBy Gustave-Claude-Etienne Courtois |

After Leland Jr. died, his parents commissioned post-homous portraits and a death mask to grieve, accept, and memorialize the two-short life of their son. The Stanfords engaged deeply with the Victorian culture of mourning, which was perpetuated by high mortality rates of the era. The death mask was made directly from the face of the deceased and cast in plaster or a similar material. Photographs and death masks were often used to generate the posthumous portraits the celebrated the dead. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Goldsmith Maid Driven by Budd Doble, 1876Oil on canvasBy Thomas Kirby Van ZandtUSA 1814-1886 |

Palo Alto Spring, 1878Oil on canvasBy Thomas HillUSA, b. England, 1829-1908 |

|

|

|

|

Viktoria, 1999Unique cast bronzeDeborah Butterfield U.S.A. b.1949Deborah Butterfield studied art at the Ubiversity of California at Davis before moving to a ranch in Bozeman Montana in 1976. Since then she has focused solely on the subject of the mare, producing six to ten horses each year in an inexhaustible exploration of the material and form. With each sculpture, Butterfield endows the animal with its own unique and complex personality that is dependent on the materials she uses and on her mood as she is working; these materials have included mud, wire, twigs, found metal, and bronze.Viktoria was cast in bronze from an original model made of driftwood. The technique is especially notworthy for its striking resemblance to wood's natural texture, shape, and color. In this particular horse, Butterfield captured the gesture, power, and beauty as in a classical equestrian study. |

Viktoria, 1999Unique cast bronzeDeborah Butterfield U.S.A. b.1949 |

Vairochana(Chinese:Palushena, Japanese:Birushana)Copper alloyChina, Ming dynasty (1368-1644)Vairochana (the "Illuminator," literally "Coming from the Sun") is one of five Transcendent or Dyani Buddhas. Here, he is depicted as described in the Brahmajalasutra, seated upon a lotus with a 1,000 petals thaat emit 100,000 Buddhas, each of whom will teach the doctrine to a different universe. |

Death of the Buddha (Parinirvana)15th centuryWood, gesso, gold, lacquer, and pigmentArtist unknownChina, Ming dynasty (1368-1644) |

|

Tsongkhapa18th centuryGilt copperMongolia |

|

May 10, 2018–February 25, 2019In this exhibition, artist Do Ho Suh uses a chandelier, wallpaper, and a decorative screen to focus attention on issues of migration and transnational identity. Using repetition, uniformity, and shifts in scale, Suh questions cultural and aesthetic differences between his native Korea and his adopted homes in the United States and Europe. The wallpaper Who Am We? (Multi) (2000) is made up of miniaturized yearbook portraits of the artist’s high school classmates, a nostalgic gesture that points both to the social connections of childhood and an immigrant’s estrangement from peers. While screens often decorate and divide Korean interiors, the many small figures that comprise Screen (2005) are used to examine opacity and transparency, division and connection, privacy and togetherness. The chandelier Cause and Effect (2007), composed of many figures appearing to rise from the shoulders of the single figure at bottom, playfully suggests that no matter where we travel, we carry the weight of our pasts on our shoulders.Text from: Cantor Arts Center |

Cause & Effect 2007Acrylic, aluminum, disc, stainless steel frame, stainless steel cable, and monofilamentDo Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962) |

Detail of: Cause & Effect 2007Acrylic, aluminum, disc, stainless steel frame, stainless steel cable, and monofilamentDo Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962) |

Detail of: Cause & Effect 2007Acrylic, aluminum, disc, stainless steel frame, stainless steel cable, and monofilamentDo Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962) |

Screen, 2005ABS and stainless steelDo Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962) |

Screen, 2005ABS and stainless steelDo Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962) |

Screen, 2005 |

|

Screen, 2005ABS and stainless steelDo Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962) |

|

|

|

Dragon, 19th centuryCrysral, bronze, and silver-giltJapan, Meiji period (1868-1912) |

Dragon, 19th centuryIvoryJapan, Meiji period (1868-1912)Articulated mental dragons were popular during the Meiji era. This most unusual example is composed of 134 seperate pieces, held together by a spring system; the claws, mouth, tongue, and horns are moveable as well as the bady and legs. |

Detail of: Dragon, 19th centuryIvoryJapan, Meiji period (1868-1912) |

Detail of: Dragon, 19th centuryIvoryJapan, Meiji period (1868-1912) |

Woman with AttendantsCoralChina, 20th century |

VaseRock crystalChina Ming dynasty (1368-1644) |

Cause & Effect 2007Acrylic, aluminum, disc, stainless steel frame, stainless steel cable, and monofilamentDo Ho Suh (South Korea, b. 1962) |

|

|

Chinesca Kneeling Woman 100 BCE-250 CEPolychrome ceramicArtist unknownNayarit, Mexico |

Seated Figure 900-1000Polychrome ceramicArtist unknownColima, Mexico |

Joined Male and Female Couple 100 BCE-250 CEPolychrome ceramicArtist unknownNayarit, Mexico |

Pair of Seated Figures 250-500Polychrome ceramicArtist unknownJalisco, Mexico |

Kneeling Blind Woman, Warrior, Dog, Figure Playing Rasp, Seated Prisoner100 BCE-250 CEPolychrome ceramicArtist unknownNayarit, Mexico |

Sacrifice Scene 250-500Polychrome ceramicArtist unknownVeracruz, Mexico |

Sacrifice Scene 250-500Polychrome ceramicArtist unknownVeracruz, Mexico |

Main Lobby of the Cantor Arts Center |

|

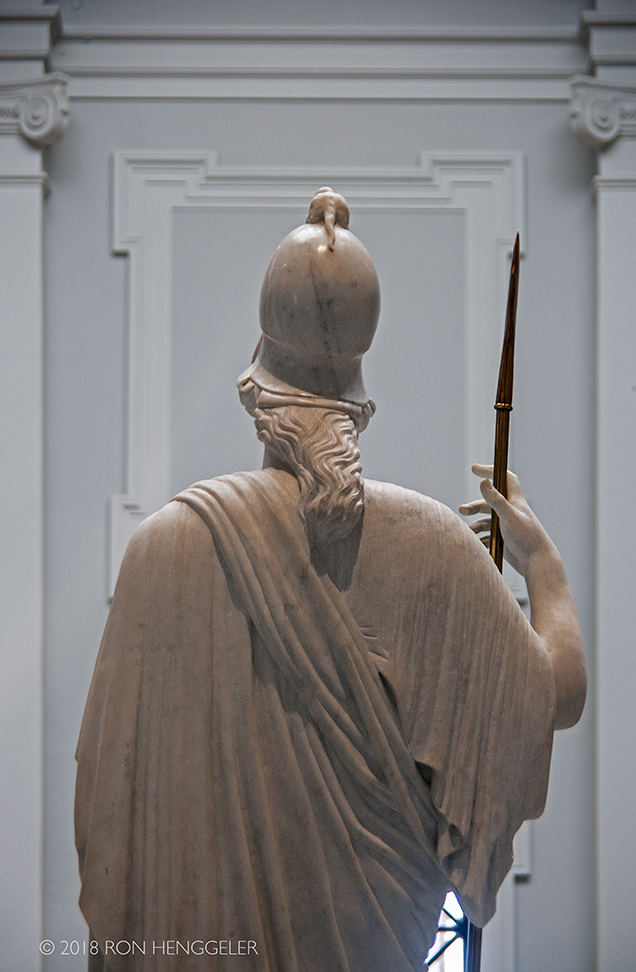

Minerva Giustiniani, c.1890Marble with brass spearAntonio FrilliItaly 1835-1892Frilli's statue is a replica of a 2nd century Roman versin of a Greek bronze of the 4th century B.C. First documented in the Giustiniani collection in 1631, the statue was reputedly excavated from a site near an ancient Roman temple of Minerva. Thought to be a rare cult figure and not just a work of art, it gained popular renoun. In addition, its austere beauty supported the theory that it derived from the statue of Athena made by Phidias for the Parthenon. In 1805 the Giustiniani family sold the Minerva to Lucien Bonaparte who in turn sold it to Pope Pius VII in 1817 for the Vatican Collection, where it remains today. |

|

Minerva, the Roman counterpart to the Greek goddess Athena, is the goddess of wisdom, the arts, and justice. She wears a helmet and bears a spear in her role as patroness of justified wars. the snake beside her may allude to Erichthonius, the mythical first king of the city of Athens whom the goddess had reared. As depicted on a Greek vase in the Staatliche Museum, Berlin, he is characterized as a serpentine being. Around Minerva's neck is the aegis, a protective collar described by the Roman author Virgil as "a fearsome thing with a surface od gold-like scaly snake-skin." Forged by the god Hephestus, Athena later afixed the head of Medusa to it. |

Kitchen Pieces, 1890Oil on canvasRichard La Barre GoodwinU.S.A. 1840-1910 |

|

Minerva, the Roman counterpart to the Greek goddess Athena, is the goddess of wisdom, the arts, and justice. She wears a helmet and bears a spear in her role as patroness of justified wars. the snake beside her may allude to Erichthonius, the mythical first king of the city of Athens whom the goddess had reared. As depicted on a Greek vase in the Staatliche Museum, Berlin, he is characterized as a serpentine being. Around Minerva's neck is the aegis, a protective collar described by the Roman author Virgil as "a fearsome thing with a surface od gold-like scaly snake-skin." Forged by the god Hephestus, Athena later afixed the head of Medusa to it. |

Fight between Dogs and Bear 1602-57Oil on canvasArtist unknownFlanders, active 17th centuryafter Frans SnydersFlanders, 1569-1657 |

Dog with head of an Ox, 1602-57Oil on canvasFrans SnydersFlanders, 1569-1657 |

St. Sebastian Attended by Irene, 1615-16Oil on canvasNicolas RegnierFrance, c.1590-1667 |

|

The Thinker 1903BronzeAuguste Rodin(1840 -1917)Weighing in at approximately one ton and measuring more than 6 feet tall in a seated position, this iconic work by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin commands center stage in the Diekman Gallery.When conceived in 1880 in its original size (approx. 70 cm) as the crowning element of The Gates of Hell, seated on the tympanum, The Thinker was entitled The Poet. He represented Dante, author of the Divine Comedy which had inspired The Gates, leaning forward to observe the circles of Hell, while meditating on his work. The Thinker was therefore initially both a being with a tortured body, almost a damned soul, and a free-thinking man, determined to transcend his suffering through poetry. The pose of this figure owes much to Carpeaux’s Ugolino (1861) and to the seated portrait of Lorenzo de’ Medici carved by Michelangelo (1526-31).While remaining in place on the monumental Gates of Hell, The Thinker was exhibited individually in 1888 and thus became an independent work. Enlarged in 1904, its colossal version proved even more popular: this image of a man lost in thought, but whose powerful body suggests a great capacity for action, has became one of the most celebrated sculptures ever known. Numerous casts exist worldwide, including the one now in the gardens of the Musée Rodin, a gift to the City of Paris installed outside the Panthéon in 1906, and another in the gardens of Rodin’s house in Meudon, on the tomb of the sculptor and his wife. |

Household Find, 1990Ironing board, tin, wood, and PlexiglasWillie ColeU.S.A. b. 1955 |

Soundsuit, 2015Mixed media, including beaded and sequined garments, fabric, hair, and found objectsNick CaveU.S.A. b. 1959 |

Soundsuit, 2015Nick CaveU.S.A. b. 1959 |

Detail of: Soundsuit, 2015 |

Detail of: Soundsuit, 2015 |

Detail of: Soundsuit, 2015 |

A view of the McMurtry Family Terrace from the Freidenrich Family Gallery at the Cantor Art Center |

McMurtry Family Terrace at the Cantor Art Center |

Detail of: Minerva Giustiniani, c.1890Marble with brass spearAntonio FrilliItaly 1835-1892Frilli's statue is a replica of a 2nd century Roman versin of a Greek bronze of the 4th century B.C. First documented in the Giustiniani collection in 1631, the statue was reputedly excavated from a site near an ancient Roman temple of Minerva. Thought to be a rare cult figure and not just a work of art, it gained popular renoun. In addition, its austere beauty supported the theory that it derived from the statue of Athena made by Phidias for the Parthenon. In 1805 the Giustiniani family sold the Minerva to Lucien Bonaparte who in turn sold it to Pope Pius VII in 1817 for the Vatican Collection, where it remains today. |

Detail of: Minerva Giustiniani, c.1890Marble with brass spearAntonio FrilliItaly 1835-1892 |

|

Stanford University is the home to the core of the Anderson Collection, one of the world’s most outstanding private assemblies of modern and contemporary American art.The collection is a gift from Harry W. and Mary Margaret Anderson and Mary Patricia Anderson Pence, the Bay Area family who built the collection over the last 50 years.The Anderson Collection at Stanford University is adjacent to Cantor Arts Center and the McMurtry Building for the Department of Art and Art History, and across Palm Drive from Bing Concert Hall and Frost Amphitheater. The addition of this remarkable art collection strengthens Stanford’s growing commitment to the arts and the connection between the study, creation and experience of arts. |

Richard Olcott of Ennead Architects is the designer of the Anderson Collection at Stanford University; he and partner Timothy Hartung, with whom he recently completed Stanford’s Bing Concert Hall, lead the Ennead team.The design for the Anderson Collection locates exhibition spaces on the second floor below an undulating ceiling. The gentle slope of the ceiling and the continuous translucent clerestory at the perimeter of the building bring diffused natural light into the galleries from above. A grand central staircase extends the gallery walls, allowing visitors to view art as they gradually ascend from the lobby to the main galleries above. Openings between the gallery walls provide views into the double height stair hall, which serves as a point of orientation for visitors circulating throughout the building. A primary goal of the design has been to translate and interpret the unique accessibility to the art as it has been exhibited throughout the Anderson’s home and offices and foster a similar powerfully direct and intimate experience. The gallery layout is conceived as one open room, freeing visitors from a prescribed sequence and promoting the exploration of individual interests.The second floor gallery volume cantilevers over the first floor to create a modern interpretation of Stanford’s traditional pedestrian arcade, extending along the south side of the building towards an intended contemporary sculpture garden. The building program is positioned to activate the pedestrian walkway; large windows offer views into the library, gallery and academic spaces that fulfill the educational mission of the Anderson program to become a vital library and teaching space in addition to a gallery.Internationally-acclaimed for powerful and sustainable building designs for cultural, educational, scientific and governmental institutions, Ennead Architects (formerly Polshek Partnership) has been a leader in the design world for decades. |

The Anderson Family and the CollectionThe Andersons' criteria for collecting is"Have we seen it before, and could we have thought of it?" |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Stanford Mausoleum |

What You Don't Know About...The MausoleumBy Jenny PeggEarly versions of landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted's plans for Leland Stanford Jr. University placed a family mausoleum at dramatic focal points for which the entire campus would provide an elaborate frame. The final plan, however, saw the Mausoleum shifted just west of Palm Drive to its location near the present-day Arizona Cactus Garden, where the landscape provides a sheltered setting for Founder's Day ceremonies and Halloween bacchanalia. The tomb, completed in 1889, cost more than $100,000 (about $2.3 million today). Here are more facts crypt fans can keep in mind.Read more of Jenny Pegg's article in the Stanford Alumni Magazine here. |

Braces of sphinxes wing thee to thy rest. Jane Stanford pondered many decisions in building the Mausoleum, but one important change order involved the commission of Greek sphinxes to flank the doors. An archival document notes that Mrs. Stanford, upon seeing the woman/lion statues, "found the artistic effect not pleasing." The buxom sphinxes were moved to the back of the building, and more androgynous specimens were installed up front.From the article by: Jenny Pegg |

|

|

|

Adjacent to the Mausoleum one will find the Stanford Family statue, cast in bronze in 1899 by Larkin G. Mead. This memorial to the family was originally placed in Memorial Court but has since had several homes on campus. Restored in 1982, it was relocated to its current position in 1998. |

Stanford Resurrects Statue of Founding Family / Politics kept bronze stored for 20 yearsMichaela Jarvis, Chronicle Staff WriterSaturday, June 20, 1998Having survived a fight over gender politics, a thumb amputation and 20 years in storage, a nearly 100-year-old bronze statue of Stanford University's founding family finally found its way back to public display in 1998.The statue was placed next to the Stanford Mausoleum after nearly a century of being moved around campus. Its latest relocation brought the statue out of the obscurity imposed after a 1987 controversy. At that time, Stanford feminists objected to how the statue portrayed university co-founder Jane Lathrop Stanford. To read the SF Chronicle article by Michaela Jarvis, go here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Detail of the bronze doors od the Stanford Mausoleum |

|

|

|

Gay Liberation, 1980Painted bronzeGeorge SegalU.S.A. 1924-2000 |

|

Gay Liberation by George Segal at Stanford University To read more about this statue, its controversy and repeated vandalism, go here. |

|

|

Dave and Jane |

Dave, Jane, & Ron |

Newsletters Index: 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006

Photography Index | Graphics Index | History Index

Home | Gallery | About Me | Links | Contact

© 2019 All rights reserved.

The images are not in the public domain. They are the sole property of the

artist and may not be reproduced on the Internet, sold, altered, enhanced,

modified by artificial, digital or computer imaging or in any other form

without the express written permission of the artist. Non-watermarked copies of photographs on this site can be purchased by contacting Ron.